Opinion

Arms Bearing And The Nigerian Reality

By Zainab Suleiman Okino

On Saturday, June 25, a colleague sent some disturbing pictures and material to me for publishing.

The images were reminiscent of a war situation – of people in long queues with a few salvaged belongings; babies strapped to their mothers’ backs; little ones managing to pace up with their parents; placard-carrying teenagers in staged, meek protest; overloaded Volkswagon golf cars, and other pictures of a subdued town that had just been deserted.

Welcome to Mada town in Zamfara, though not officially at war, but whose residents, nevertheless, had to flee their ancestral homes because of incessant attacks and abduction of people of that town.

A day after the Mada exodus, on June 26, the governor of the State, Bello Matawalle anounced some counter-banditry measures that have got Nigerians arguing over the propriety of the proposed measures.

For many parts of Zamfara State, the Mada story is their lot. We can at best sympathise with the people, but the governor of the State, whose responsibility it is to provide security and succour, is no longer at ease.

He can no longer rely on Abuja’s assurances and arms provision steeped in controversy; he must have run out of patience in pacifying the bandits, who terrorise and enforce levies on innocent communities, maim and rape men and women.

He came up with an answer many are not comfortable with, but as the saying goes, an unpalatable solution might be better than none.

As such, when the government of Zamfara State asked “individuals to prepare and obtain guns to defend themselves against the bandits and it (government) is ready to facilitate such, especially for farmers to secure basic weapons”, and claimed to have “concluded arrangements to distribute 500 forms to each of the 19 emirates” and establish a “centre for the collection of intelligence”, hell was let loose among Nigerians on its practicability.

And the fact that it is a violation of the constitutional provision against arms bearing by just anyone in the country.

Sadly, what the governor thought was a good approach — that certain categories of people should carry arms to defend themselves and their communities — has been met with mixed reactions.

For the Federal Government, as represented by the Chief of Defence Staff (CDS) Lucky Irabor and the commissioner of Police in the State, the governor has overstepped his boundaries, in a faulty federation that makes it impossible for the commissioner of Police to take orders from the governor of a State he is serving in, especially if that State is in a opposing political party.

The governor is in a catch-22 situation. Imagine the desperation and helplessness that must have driven the State governor to this level of action or statement, which has a lot of implications for personal safety, state and national security.

Although his action can boomerang on his preeminent position as governor, all the acclaimed efforts of the Federal Government have not guaranteed security for the people. Supposedly in charge of the security of all, the Federal Government has failed, and the governor’s proposal is a vote of no confidence on the central Government’s unified security architecture.

No matter how we try to couch it, this federation has failed, can no longer serve the purpose of its establishment, and has negated the spirit and purpose of government. Conversely, this glaring failure is indirectly a reason for the opposition to the Zamfara proposal, on which many of the tongue-in-cheek apologists of the failed federal state are anchoring their views.

Apart from the fact that self-help can leave all of us with bloody noses, the method that the governor is proposing to apply is akin to having communities take responsibility for their protection.

Yet, these same politicians — including Matawalle — are averse to the devolution of powers, especially between the State and local governments, as an integral part of a holistic structural change that might make it impossible to come to share the Federation Account Allocation Committee (FAAC) money in Abuja monthly.

Or allow local governments to function independently, obviously because they have no innovative or entrepreneurial skills to turn their states around.

Meanwhile, there is a semblance of ‘state police’ in almost all the states of the federation, where all sorts of vigilante groups exist, which sometimes organise, defend, and protect these governors’ interests, especially at critical periods of electioneering campaigns and election rigging.

There is Hisbah in Kano; they apprehend people who run foul of the law and criminals. There are LASTMA, LAWMA, KAI and even a powerful non-state actor, Olumo’s group in Lagos; groups that are feared and respected more than the police.

What is therefore the role of political leaders? Just to live in luxury, drive about in posh cars, build expensive mansions, and travel to exotic destinations around the world?

So, in one breath, governors do not want powers devolved and local government autonomy, yet the Zamfara governor is proposing to “distribute 500 forms to each of the emirates in the state for those willing to obtain guns to defend themselves”. This may just be the beginning of the implementation of state-controlled policing by other means.

Matawalle’s proposal is not such a call to anarchy, as it is a call for introspection, for a revision of a system of government that is clearly not serving anyone well; a system that has failed in its core mandates of providing welfare, security, and the protection of lives and property of citizens.

Unfortunately, the supposed solution is coming rather late and is almost incapable of nipping banditry in the bud, at a time it has become a transactional and thriving industry, and at a time Zamfara people are deserting their homes, having run short of means of paying ransom to abductors.

Besides, how would the people acquire the suggested arms when they cannot even meet their basic needs?

Matawalle’s recipe also reminds us of the South-West security outfit, Amotekun, which though controversial at inception, has since been modified to work with the police to achieve more successes in terms of security, and is not doing badly.

So far, the South-West is about the “safest” part of the country, not only because of Amotekun, but also because the South-West elites are proactive and try to get to the root of disturbing issues before they become hydra-headed. What is Amotekun, if not a form of community policing?

As it was with the introduction of Amotekun, with a bit of modification and little resistance from the Federal Government, so shall state and community police come to stay, in piecemeal in the country, without necessarily calling it by its name. It might just be the sensible way out of our security quagmire.

Those who oppose states or local governments having their own security arrangement will soon begin to accept the reality of its necessity.

I was once on a trip to Gembu in Sardauna Local Government of Taraba State. One of our journalist-hosts told us of how it used to take days for people to travel from that part of the country to their capital, Yola, when Taraba was still under the old Gongola State.

He also said that it would take just about 15 minutes to get to Cameroon from Gembu, whereas it took us more than seven hours to travel from Jalingo, the capital of Taraba State to the same Gembu.

Notwithstanding the historical efforts made by the late Premier of Northern Nigeria, Sir Ahmadu Bello, in the plebiscite leading to the ceding of that part of Taraba to Nigeria, I felt it for the people of Sardauna Local Government, who are almost cut off from the Nigerian civilisation, because of its hard-to reach location.

In an event of conflict in that area, as it happened recently, not even the State government in Jalingo can easily mobilise to their rescue. Does it then make sense for Nigerian citizens there to continue to depend on, not even Jalingo, but Abuja for their protection?

Despite all odds, I salute the courage of Governor Matawalle for the reality check and for localising an intractable challenge that has almost consumed Zamfara State. He has set the ball rolling so to say, but the task is more daunting than it seems. However, once there is the will, there will always be a way. If this had happened earlier, the people of Mada, referred to above would not have deserted their town. With support from the State, they would have secured themselves and their town.

Zainab Suleiman Okino is the Chair, Editorial Board of Blueprint newspaper. She can be reached through zainabokino@gmail.com

Opinion

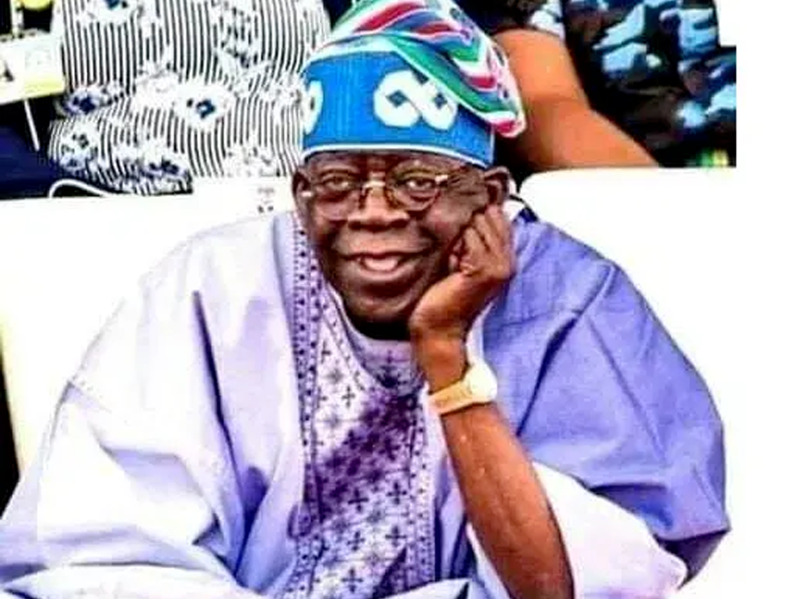

Tinubu’s Dark Mercy: How Presidential Pardon Turned Justice Into A Joke

By Ademola Adekusibe

Something snapped in Nigeria yesterday. It wasn’t just the announcement that President Tinubu had pardoned 175 convicts; it was the final confirmation that in this country, crime no longer carries consequence. It was the state’s open confession that Nigeria’s justice system is now a casino, and those with connections always win.

Let’s start with one name that should haunt every soldier who ever wore the uniform: Major Suleiman Alabi Akubo. In 2008, a military court didn’t just find him guilty; it laid bare the horror of his betrayal. The man stole 7,000 weapons from the Nigerian Army, weapons meant for the nation’s defense, and sold them to militants who turned them on his own comrades. Soldiers died. Innocent Nigerians died. The country bled. And the General Court Martial, in its rare moment of courage, sentenced him to life imprisonment.

That was supposed to be justice. That was supposed to be a warning that no one, no matter how decorated, could betray the flag and walk free. But now, the same Nigeria whose sons were buried by bullets he sold has opened the prison gates and called it “presidential mercy.” Mercy for treason. Mercy for blood money. Mercy for a man whose greed armed killers and destabilized the nation.

If this is mercy, then what do we call justice?

And then there’s Maryam Sanda, a woman who, by her own actions, turned her matrimonial home into a slaughterhouse. The night she killed her husband wasn’t an accident; it was a progression of rage, five failed attempts before the fatal strike. The court found her guilty of culpable homicide and sentenced her to death by hanging. Nigerians thought it was closure. The law had spoken. But in this new Nigeria, even murder has an escape route, a back door guarded by sympathy, privilege, and presidential benevolence.

Today, she walks free. Her victim remains six feet below, voiceless, silenced forever. Is this how we honour the dead? By setting their killers free in the name of “mercy”? If Maryam Sanda deserves pardon, then what message are we sending to every man or woman enduring domestic violence? That if their abuser kills them, justice can later be undone with a signature?

And this isn’t even about two names. The rot runs deeper. Among those granted clemency were illegal miners, men who have turned parts of Zamfara and Niger State into killing fields. They were handed over to a politician, yes, a politician, as though the state were transferring cattle, not convicts. Do we even realize how insane that sounds?

Then there’s the drug traffickers, the billion-naira fraudsters, and bribe-takers like Farouk Lawan, once caught stuffing $500,000 into his agbada like a man packing sin into his conscience. They, too, found mercy. While ordinary Nigerians sit in jail for stealing yams, the powerful steal nations and go home with presidential blessings.

What sort of country pardons a man who sold weapons to militants but keeps forgotten prisoners locked up for years without trial? What manner of justice rewards murder with mercy but starves the poor of fairness? If clemency is now a luxury reserved for those whose crimes shook the nation, then we have entered the age of moral bankruptcy.

This isn’t compassion. It’s corrosion. It’s the state officially declaring that morality is negotiable, that you can destroy lives, arm terrorists, betray your country, and still find redemption as long as the corridors of power recognize your name.

And perhaps the cruelest part? The families of the victims, the widows, the orphans, the soldiers who died holding their rifles against bullets sold by Akubo, were not even consulted. Justice wasn’t just denied; it was mocked.

So yes, call it “Presidential Pardon” if you must, but let’s say what it truly is: a betrayal of every honest man who ever stood for something in this country. A message to every Nigerian that the law is not a moral compass, it’s a privilege card.

Tomorrow, when another officer sells arms to insurgents, when another wife kills her husband, when another politician embezzles billions, and we ask, “Why are people this reckless?” the answer will stare us in the face: because the system rewards the wicked and excuses evil when it’s done in expensive English.

This wasn’t mercy. This was moral suicide.

Credit: The Yoruba Times

Opinion

Nigeria @65: A Nation At a Crossroad Between Celebration, Reflection

By Alao Adamadamosi Sunday, arpa

As Nigeria marks its 65th year of independence, citizens and leaders are grappling with a complex question: Is this an anniversary to celebrate, or a moment for sober reckoning?

Today, Nigeria celebrates 65 years of freedom from British colonial rule. The day is marked by a national holiday and is traditionally a time for parades, cultural shows, and presidential addresses .

However, the festivities are set against a backdrop of deep-seated challenges, prompting a national conversation on the very essence of the nation’s progress.

In his 65th Independence Day address, President Bola Tinubu struck a resolutely optimistic tone, declaring that the “worst is over” for Africa’s most populous nation.

He defended his administration’s contentious economic reforms, including the scrapping of fuel subsidies and the unification of foreign exchange rates, describing them as painful but necessary steps to “reset” the economy.

The president presented a suite of economic indicators to bolster his claim that the seeds of these reforms are now “bearing fruits”:

· Economic Growth: The second-quarter GDP grew by 4.23%, the fastest pace in four years.

· Falling Inflation: Inflation has declined to 20.12% in August, the lowest in three years, though it remains high.

· Trade Surplus: The country has recorded five consecutive quarters of trade surpluses, selling more to the world than it buys.

· Rising Reserves: External reserves have climbed to $42.03 billion, the highest level since 2019 .

This narrative of progress was echoed by government supporters. The Governor of Ogun State, Dapo Abiodun, spoke of “the enduring spirit of unity, resilience, and hope,” urging citizens to “look forward with optimism”.

Despite the official optimism, a chorus of critics and stark data points to a far more challenging reality for millions of Nigerians. A poignant editorial framed the nation’s condition as one of “independence without nationhood,” arguing that the dream of a unified, prosperous nation remains elusive 65 years on.

The challenges are profound:

Deepening Poverty: A World Bank report noted that over 54% of Nigerians live in poverty, with the rate soaring to 75.5% in rural areas . Other estimates suggest over 129 million Nigerians—more than half the population—live below the poverty line.

· Staggering Infrastructure Deficit: The country requires an estimated $3 trillion over the next 30 years to close its infrastructure gap. Notably, Nigeria has the largest electricity access deficit in the world, with 43% of its population (85 million people) lacking access to grid electricity.

· Ongoing Security Challenges: The nation continues to battle terrorism, banditry, and kidnapping, ranking sixth in the 2025 Global Terrorism Index . While the government claims security is improving , these threats remain a daily reality for many.

· A “Brain Drain”: Reflecting a loss of confidence in the system, data shows a significant increase in migration, with over 3.6 million Nigerians emigrating between 2022 and 2023 alone.

This divergence between official statements and public perception was symbolized by the federal government’s decision to cancel the official Independence Day parade, a move some interpreted as an acknowledgment that all is not well.

The cancellation of celebrations, as interpreted by cleric Prophet Sam Ojo, is a sign that “Nigeria needs healing”. This sentiment resonates with those who believe the path forward requires more than economic metrics.

Many analysts argue that Nigeria’s fundamental ailment is structural. The country has been attempting to govern its vast diversity of over 250 ethnic groups through a “largely unitary system” that stifles development and fuels resentment among regions feeling exploited or marginalized.

The solution, they propose, is an urgent return to true federalism—devolution of power to the constituent units to foster competition, accountability, and a sense of belonging .

As Nigeria steps into its 66th year, the dual narrative of progress and pain defines its independence anniversary. The government points to macro-economic green shoots, while citizens grapple with the daily challenges of survival.

The nation stands at a crossroad, and the most pressing task may be to bridge the gap between statistical recovery and the lived experience of its people, forging not just an independent state, but a true nation where every citizen can find “purpose and fulfilment” .

As we mark another October 1st, may this not just be a ceremonial celebration but a reminder of the work still ahead for leaders to act with integrity and for citizens to demand accountability.

Opinion

Benue Killings: Is This The President You Endorsed? (OPINION)

As Nigeria reels from yet another wave of bloodshed in Benue State—where recent gunmen attacks left more than 150 villagers dead, many burned alive in their homes—the nation’s attention turns, inevitably, to the man in whose name we voted: President Bola Ahmed Tinubu.

The unfolding tragedy in Benue is not an isolated outbreak of violence, but rather a grim symptom of a broader malaise: a leadership marked by performative gestures, political expediency, and a troubling paucity of empathy.

ABSENCE OF EMPATHY: THE MOKWA FLOOD AS PRELUDE

In late May 2025, torrential rains unleashed catastrophic flooding in Mokwa, Niger State. Over 200 lives were lost, hundreds of homes were submerged, and critical infrastructure—roads, bridges, markets—was swept away.

Yet, when President Tinubu’s condolences were needed most, it was Vice‑President Kashim Shettima who sat before distraught survivors, pledging federal relief on the President’s behalf.

Despite announcing a ₦2 billion reconstruction fund and dispatching 20 food‑loaded trucks, Mr Tinubu himself remained at his desk in Abuja, delegating his presence to envoys rather than offering the solace of personal solidarity. This physical absence was more than mere logistics; it set a tone.

When the country is in pain, its leader’s first act of compassion should be to stand among the afflicted. Instead, Nigeria witnessed a head of state whose body language signaled distance, if not detachment.

President Tinubu’s detachment in the aftermath of the Mokwa flood was not an isolated occurrence, but rather a continuation of an unsettling pattern of presidential absence during national tragedies.

One of the earliest examples came in June 2023, when a boat accident on the Niger River in Patigi, Kwara State, claimed the lives of over 100 wedding guests.

The tragedy shocked the nation and drew widespread media attention, yet President Tinubu neither visited the victims’ families nor made a physical appearance at the scene. His condolences came via a written statement, which many described as impersonal and formulaic.

Similarly, in September 2023, when flooding displaced thousands in Bayelsa and Kogi States, President Tinubu once again failed to show up in person.

Despite mounting public pressure and calls from local leaders for federal presence, the President remained in Abuja, directing federal agencies from afar and relying on surrogates to visit displaced persons.

These instances—prior to the Mokwa flood—suggest that the President’s current pattern of governance tends to avoid the emotionally resonant act of being present.

POLITICAL CALCULUS OVER HUMAN LIVES

While entire communities in Mokwa and Benue were grappling with loss, the President and his All Progressives Congress (APC) were already pivoting toward re-election strategising.

On May 22, 2025, barely weeks after accepting the mantle of national mourning, the APC officially endorsed Tinubu as its sole candidate for the 2027 presidential race—a ceremony replete with promises of economic continuity and reform.

Yet never once did the party pause to address the urgent insecurity that was devouring farms, markets, and families.

The optics are stark: while children and the elderly perished in unnamed villages, APC governors draped themselves in campaign paraphernalia, unaware—and perhaps uncaring—that their mandate to protect was being squandered in favor of political theater.

EMPTY WORDS ON THE ASHES OF BENUE

When gunmen descended on the Yelewata community in Guma LGA, sparing neither women nor children, President Tinubu’s preferred mode of engagement was a scripted condemnation via press statement.

“I will adjust my schedule to visit Benue people on Wednesday,” he declared, promising a personal visit to assess the damage.

The charred husks of homes and commerce in Benue stand as a mute reproach to a leader whose words betray no trace of sorrow in his countenance.

An authentic leader would have gone beyond televised sound bites, immersing himself in the grief of survivors—the orphaned children, the widows, the displaced—bearing witness to the human cost of insecurity under his watch.

GOVERNORS’ ENDORSEMENTS: A PARADOX OF LOYALTY

Perhaps the most poignant indictment of Tinubu’s presidency is the chorus of APC governors rallying behind him for a second term.

In the same breath that they praise his “economic reforms,” they ignore the fact that inflation has soared past 23 percent, that food security is now a privilege rather than a right, and that Nigerians no longer feel safe in their own communities.

This display of political loyalty, untempered by accountability, forces a question: when did governance become synonymous with uninterrupted tenure rather than service to the people?

At what point did infrastructure ribbon‑cuttings eclipse the imperative to safeguard lives?

THE BURDEN OF CHOICE

When Nigerians cast their votes in February 2023, many yearned for a president who would not only talk about reform but also personify compassion, decisiveness, and a hands‑on approach to crisis.

Instead, two years into his term, President Tinubu has cultivated an image of a distant executive—adept at policy pronouncements and partisan maneuvering, yet reluctant to walk the ground where suffering is most acute.

As the smoke still rises from the ruins of Yelewata, and as survivors grapple with loss, the nation must reckon with a disquieting reality: the leader we endorsed appears more committed to cementing political power than mending broken communities.

In the balance between campaigning for a second term and delivering on the most basic duty of governance—protection of citizens, the latter has been glaringly neglected.

Is this the president you endorsed? As Benue burns, and as the echoes of unfulfilled promises linger, this question demands not just a simple yes or no, but a collective reckoning on the values and expectations that guide our democracy.

Credit: Pulse (17 June 2025)

-

News1 year ago

News1 year agoKogi Police Prohibits, Warns Against Use of Vehicles With Covered Number Plates

-

News1 year ago

News1 year agoHow We Discovered Drugs In The Residence of Kwara Senator Accusing Us of Corruption. – NDLEA

-

News2 years ago

News2 years agoKogi Govt. Commences Staff Audit For State Civil Servants Dec. 5th

-

Politics2 years ago

Politics2 years agoKOGI2023: AA’s Candidate, Braimoh, Promises To Regenerate State’s Economy, Receives Decampees

-

News2 years ago

News2 years agoPDP Will Expel Wike At Appropriate Time – Bwala

-

News3 years ago

News3 years agoWAEC Releases 2022 WASSCE Results

-

Solicited2 years ago

Solicited2 years agoYAHAYA BELLO: The Generalissimo!

-

News3 years ago

News3 years agoSen. Smart Adeyemi Set To Kick-off N250M Empowerment Programs In Kogi West